Murders Around Mississippi

Newest information on Mississippi murders involving African Americans and/or Mississippi politicians and leaders. SYNDICATE SUSAN'S ARTICLES on your site! Fast, Easy & Free! (El Movimiento por los Derechos Civiles en Estados Unidos)Friday, February 24, 2006

Mississippi Court Denies Kennard Petition

From the Arkansas Delta Peace and Justice Center:

MS high court denies Kennard petition

The Delta Center poses these "questions about the case that should be answered and the answers published."

Who were the arresting officers?

Who was the prosecuting attorney?

Who was the presiding judge at the trial?

Who were the judges who denied the appeals?

What was the involvement of the White Citizens' Council?

Who were the leaders of the White Citizens' Council in Hattiesburg?

What was the Sovereignty Commission's involvement?

Are any of these people still living?

Can they be prosecuted?

* * * * *

If you don't know the sad story of Clyde Kennard, the following comes from "Where Rebels Roost: Mississippi Civil Rights Revisited," 2005:

Clyde Kennard of Hattiesburg was arrested September 15, 1959, for illegal possession of liquor and speeding. This happened shortly after Kennard was rejected the second time for admission to Mississippi Southern College, now the University of Southern Mississippi.

While Sovereignty Commission records show authorities once considered placing dynamite in his car (and a Hattiesburg lawyer offering to run him out of the country), the state finally succeeded in its quest to punish the poultry farmer and U. S. Army veteran when thirteen months later, on November 21, 1960, Kennard was convicted on charges of stealing chicken feed.

He was sentenced to Parchman penitentiary for the maximum penalty of seven years. Medgar Evers heard of the verdict and told a reporter Kennard’s conviction was “a mockery of justice” for which Evers was arrested, charged with contempt and sentenced to thirty days in jail. The Supreme Court later overturned the conviction.

But Kennard was literally beaten and worked to death at Parchman and after becoming seriously ill, he was diagnosed with cancer by the University of Mississippi Hospital. Returned to Parchman, Kennard was dragged out to work in the fields each day despite his growing weakness.

Prison authorities canceled his appointment for a medical checkup and he was not allowed to see his lawyer, Jess Brown. The Jackson attorney asked to receive Kennard’s medical reports but never got them.

Tougaloo students mobilized to try and free Kennard, a friend of one of their instructors. The story was picked up nationally as Dick Gregory and Dr. Martin Luther King demanded Kennard’s release.

Finally, in 1963, Governor Barnett ordered Kennard’s release, concerned over potential bad publicity for the state if Kennard died at Parchman. Kennard underwent surgery in Chicago and soon died at Billings Hospital, shortly after he was paroled.

Was it an administrative oversight? Or was it deliberate negligence because of his connection with school integration? These questions, asked by Kennard’s attorney, were never answered. “No one can say for sure. You have to draw your own conclusions,” Jess Brown said.

Clyde Kennard died at the age of thirty-six on July 4, 1963.

Footnote: In one 1959 memorandum found in Mississippi Sovereignty Commission files, commission investigator Zack VanLandingham tells of a conversation he had with a Hattiesburg lawyer, Dudley Connor, about Kennard in the late 1950s. "If the Sovereignty Commission wanted that Negro out of the community and out of the state they would take care of the situation," VanLandingham quoted Connor as saying.

"And when asked what he meant by that, Connor stated that Kennard's car

could be hit by a train or he could have some accident on the highway and nobody would ever know the difference." In another memo, written by VanLandingham to Gov. J.P. Coleman in 1959, the investigator relates a conversation he had with John Reiter, a campus police officer.

"Reiter had several weeks ago told me that when Kennard was attempting to enter Mississippi Southern College in December 1958 that he had been approached by individuals with possible plans to prevent Kennard's going through with his attempt," he wrote. "One of the plans was to put dynamite to the starter of Kennard's Mercury. Another plan was to have some liquor planted in Kennard's car and then he would be arrested."

Wednesday, February 08, 2006

Dying to Vote ...

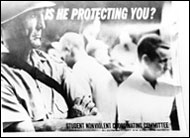

A Poster, printed by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, questions the role of the Mississippi State Highway Patrol in violence against Blacks.

Continue for details ...

Take a look - and then consider the deaths of Birdia Keglar, Adeline Hamlett and James Keglar. The two wMississippi omen, voting rights advocates, were killed in Leflore County when "their car left the road" (as reported by state highway patrolmen) on their way home from a Jackson meeting with Sen. Robert F. Kennedy.

There are so many questions about their deaths - to be answered in an upcoming book by Gary May and Susan Klopfer, "Dying to Vote." Set for publication in 2007.

You can read more about these two women at Dying to Vote in Mississippi, 3-part series.

Archives

June 2005 July 2005 September 2005 October 2005 November 2005 December 2005 January 2006 February 2006 March 2006 April 2006 May 2006 June 2006 July 2006 August 2006 October 2006 January 2007 February 2007 March 2007 April 2007 May 2007 June 2007 July 2007 September 2007 October 2007 December 2007 March 2008 April 2008 July 2008 September 2008 October 2008 November 2008 December 2008 June 2009 July 2009 December 2009 February 2010 March 2010 October 2010 June 2011

Subscribe to Comments [Atom]